Amy Moses is 25 and was born with the rare genetic condition Coffin Lowry Syndrome (CLS), which causes complex needs.

Amy lives with her parents Kerrie Thomas, 44, and Dad Nigel Moses, 51, in Gwent, Wales. When Amy was six weeks old, Kerrie saw her doctor, worried their new-born was floppy and couldn’t lift her head.

Paediatric referrals and an MRI scan followed, but it took two years for Amy to be diagnosed with CLS; her case had to be referred to geneticists in America who confirmed she had an alternation in the X-linked RSK2 gene. Tests showed Kerrie and Nigel were not carriers and Amy’s case was a one-off occurrence. Because of the continuous level of care Amy requires at home, the couple chose not to have any more children.

“For the first ten years it was a world of doctors, accessing care and occupational therapy,” Kerrie, who is Amy’s carer, says. “The doctors said they didn’t know what the future held. We never wanted to know what her life expectancy would be. Amy has learning difficulties, mobility problems, low muscle tone, incontinence, anxiety and significant speech and language delay. She also has double curvature of the spine and autism.

“Amy’s health is declining more now and it’s sad to look back at how quickly she has declined. She used to be able to walk, she could even take part at sports day at her special needs school. But now her health is worse, her eyesight and hearing are worse. Her mobility is the biggest deterioration, and she uses her wheelchair a lot of the time. She has ‘drop attacks’ where she falls to the floor, which can be so dangerous. I need to watch her all the time and I can’t leave her on her own, even to go to the toilet as she might fall and hurt herself. The drop attacks can be one after the other and can be up to 15 times a day.”

The family had a recent scare with Amy rushed to hospital struggling to breathe. She was diagnosed with sepsis, which is an increased risk for Amy as she has a compromised immune system.

When Amy reached adulthood, the family found her health needs increased just as the support they received diminished.

“As soon as your child reaches 18 or 19, all the support goes,” Kerrie explains. “Amy had an amazing paediatrician; she was under a spinal surgeon and an occupational therapist. Then at 18 that was all gone. When people say, ‘you are complaining again’, well yes, we are complaining again. We are ok, Nigel and I make a good team, but more support needs to be given to families on their knees.”

Kerrie adds: “Amy has a lot of challenges, but I don’t tend to look at the negatives. She is a happy young lady, and we focus on the special memories we can make together as a family.”

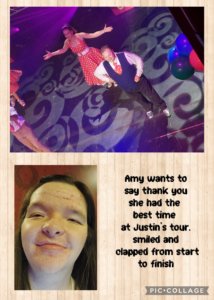

The Sandcastle Trust wanted to help the family create those special memories with Amy, through their Sandcastle Memories programme, which offers respite for families living with a genetic condition, in the form of UK breaks and days out. The charity arranged a holiday to an adapted holiday park for Amy’s family, but unfortunately it had to be cut short after one night as Amy became very unwell. The Sandcastle Trust then arranged for Amy to see her favourite TV children’s personality, Justin Fletcher, on stage in Cardiff.

Kerrie explains: “We were so deflated after having to come home early from the holiday. We were looking forward to the hydrotherapy and the sensory room, but she was very poorly. When Sandcastle called and said they wanted to help us again, I cried.

Kerrie explains: “We were so deflated after having to come home early from the holiday. We were looking forward to the hydrotherapy and the sensory room, but she was very poorly. When Sandcastle called and said they wanted to help us again, I cried.

“Amy really wanted to see Justin Fletcher. It was a win for Amy, she was so happy, and we were upgraded to a box! She was smiling when Justin was onstage, shyly waving to him, then Justin looked up and he waved at Amy. If smiles were measured in pounds, we were millionaires that day. It was absolutely wonderful. The memories mean everything.”